Exploring Cihangir and Çukurcuma: The Tale of Two Orhans

It might have been a manifestation of a long-term plan to take refuge in Turkish Summer this year but somehow, the decision to visit Istanbul for the second time in a span of three months still seemed impulsive. How Constantinople became that city for me where I would go whenever I needed to really introspect on any aspect of my life, I do not know. Maybe it is that perfect amalgamation of cultures on both European and Asian sides of the Bosphorus, or it is the assurance that nestles in every Istanbulite’s attitude that a sumptuous mildly sweet Türk kahvesi or the black çay served in the tulip-shaped see-through glass and drunk by the gallon—that can set anything straight. I cannot decide. Anyhow, on this trip, I found myself unveiling an Istanbul I had not seen before by tracing the paths led by two Turkish authors.

In his memoir, Istanbul: Memories and the City, Nobel Laureate Orhan Pamuk writes of Cihangir as the neighbourhood in which he first learned that Istanbul was not “an anonymous multitude of walled-in lives” where people remained oblivious to their respective neighbour’s activity of grieving or commemorating, but “an archipelago of neighbourhoods in which everyone knew each other”. The very quotation germinated into reality from its book form on my first night in Cihangir when I was unable to turn the key inside the worn-out doorknob of the white iron door of my apartment block in order to get to my quaint third-floor studio flat in the heart of Cihangir on Matara Sokak. An old man with kind, wise eyes came to my rescue. He spoke no English and understood in less than a second that I spoke no Turkish. The only words exchanged between us—a chorus of my Airbnb host’s name and a mandatory gratitude note to acknowledge his act of kindness, “Bahar? Bahar? Bahar?”, “Yes, Bahar!”, “Thank you!”.

I lived a street away from the modest flat on Akarsu Caddesi where Orhan Kemal, the Turkish author of short-stories and novels, lived for most of his life. It has now been transformed into the Orhan Kemal Müzesi, a wee museum where several pictures of Orhan Kemal’s life dwell with his study as he must have liked it tucked inside his room, a cluster of the first editions of his books on display (mostly in Turkish) with several items of correspondence, his death mask, and several other personal belongings. It may not be the most meticulously curated museum on a writer’s life but the reflection of the startling sincerity of the soulful life that the author must have lived, with his entire life on display, is remarkable. The museum is adjoined by a little kitabevi (bookstore) to compliment the author’s work and hosts most of his works in translation.

The path from Cihangir to Çukurcuma offers no obstacles in the outflow of cultural and historical treasure, with numerous vintage and antique shops, boutiques, cafés, bars packed with artists, writers, intellectuals and expats who consider the ritual of outdoor afternoon drinking an act of solidarity. There’s also good news for the other members of this community who do not make it out of their beds until late evening, as most joints on these café-lined cobbled streets offer “breakfast all day”.

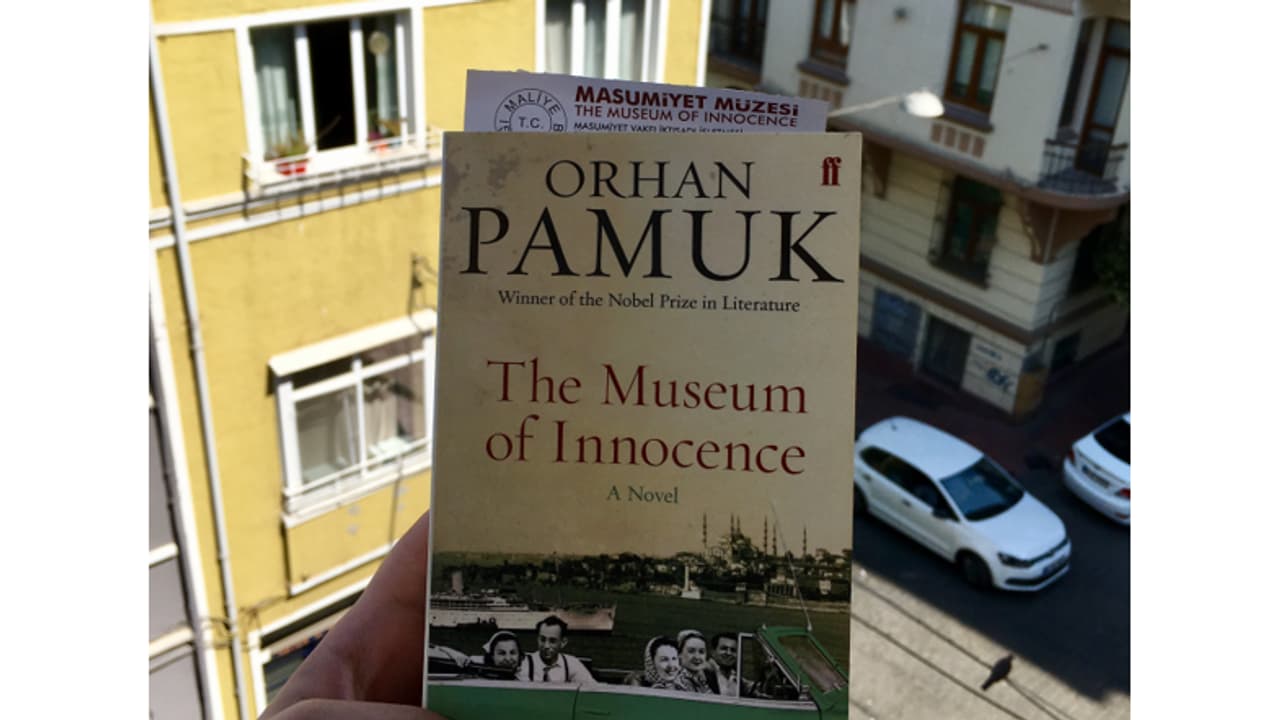

On approaching the corner of Çukurcuma Caddesi and Dalgıç Sokak, a brick-red structure stands out amid the colony of several antiquarian stores whose façades exhibit a sequence of dead dolls almost like a custom and several street art vendors attempting to lure passers-by with their own Van Gogh renditions. This 19th-century house, a brick-red structure is Masumiyet Müzesi/The Museum of Innocence, probably the only museum in the world conceptualised out of a real novel (of the same name). The Museum of Innocence does not mislead its visitor or its reader, and is not a gimmick. It is a real life physical repository of memory made tangible through the exhibition of a myriad of artefacts, “real” objects that are a part and parcel of a fictitious story of love and loss. The museum lets the visitor take a peek inside the lives of Instanbulites from the 1950s to the early 2000s.

The “material memory” plays a significant role in the novel as well and the real life museum aims at making it more vivid, letting the visitor time-travel with each step they take inside the museum, to move from one “memory box” to another, each box symbolic of each chapter in the novel. However, it must not be considered vital to have read the novel beforehand while visiting the museum and vice-versa. It is, though, interesting to observe the juxtaposition of visual understanding and text retention in the mind for a better coherent understanding of what must really have been really going on in the narratives of two separated lovers, Kemal and Füsun.

Kemal and Füsun are two distant cousins who despite the odds, fall in love. Kemal is richer and Füsun is the one who’s lesser fortunate, and marries someone else eventually. Waiting in disguise, Kemal visits her in this house (described as Merhamet Apartments in the novel) which is now this museum and where both lovers previously shielded themselves from the rest of the world, sneakily made love among the dusty remains of old furniture. Kemal continued to visit Füsun for eight years after she got married to someone else, even though she was physically never there—only her memories remained, fading with each passing day. Kemal, on each visit, took away with himself an object which collectively constituted The Museum of Innocence later.

The museum can be looked upon as a safe space created by Kemal to prove his ownership over Füsun rather than granting her the autonomy of her own life, having left her on her own devices. This is largely a representation of female identity in 1970s Turkey on the verge of getting Westernised. But at the same time, each little speck of memory in the museum speaks for the agony of bygone love with no scope of prospective return in this life. Each little speck, from a cigarette butt (There are 4213 of these!) to the lipstick that stands out on Kemal’s man-shelf, speaks poignantly for the fatality of lost love even to the non-romantics.

So, the next time you are in Istanbul, consider it wise to redeem the ticket of The Museum of Innocence printed inside the Chapter 83 of the paperback copy you own. Yes, you can get it stamped for a museum entry. Maybe while sipping a pint or two of the locally brewed Bomonti on one of the street-cafés of Cihangir, consider flipping through Orhan Kemal’s short-stories of ordinary Istanbul lives, a limited collection of them, in English, available on his website for free. Let the poetical identification with Istanbul be yours this time, like it is both Orhans’, like it is Joyce’s with Dublin. Let Istanbul’s hüzün (sadness) and mutluluk (happiness) be yours.

About Supriya

Supriya Kaur Dhaliwal is a poet and writer from the Himalayas, currently based out of Dublin. She is the author of two poetry books, The Myriad and Musings of Miss Yellow. She holds an MPhil in Irish Writing from Trinity College, Dublin. Supriya is one of the twelve poets selected for Poetry Ireland’s Introductions Series this year. She contributed to the Beckett Digital Manuscript Project in Antwerp, Belgium. Later this year, she will be joining the Seamus Heaney Centre for Poetry.

Twitter: @supriyadhaliwal

Instagram: @wooolgatherer