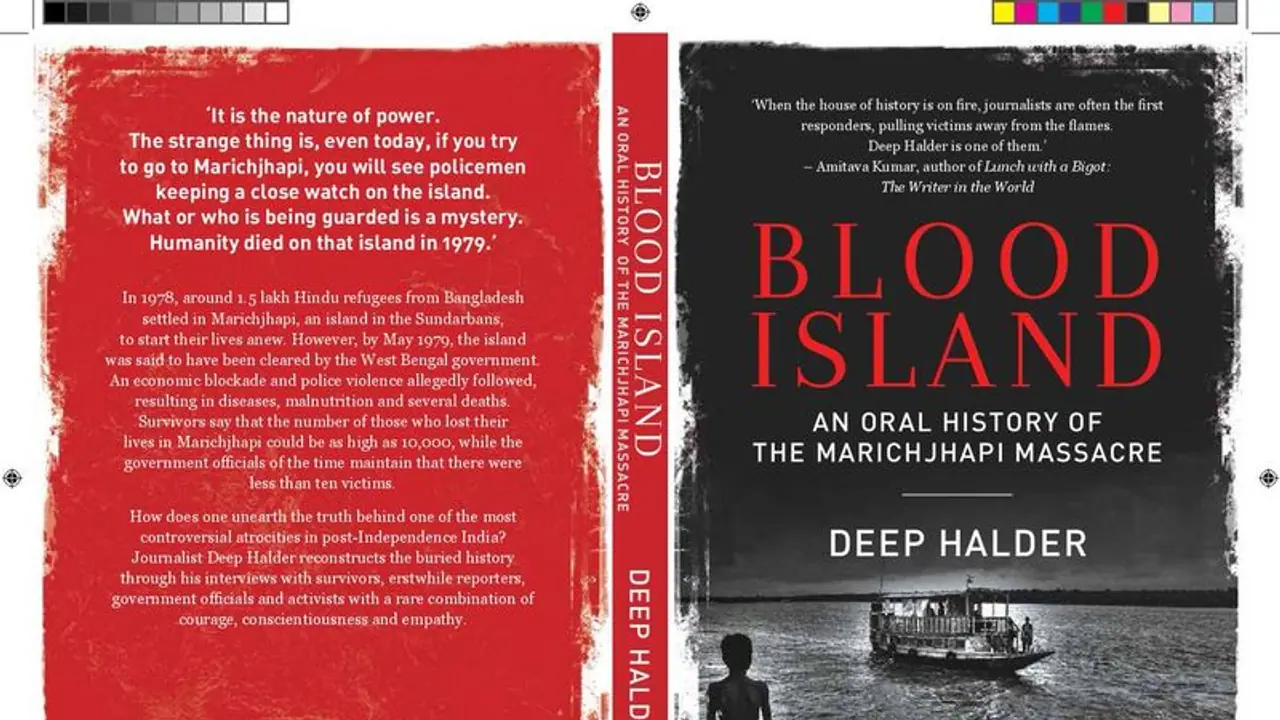

The massacre that took place in 1979 is a horrifying instance of human rights violations. Journalist Deep Halder’s book Blood Island: An Oral History of the Marichjhapi Massacre serves as a reminder of the tragedy, which has practically disappeared from public memory

Marichjhapu is a lost world. Forty-years have passed since the Jyoti Basu-led Left Front government in West Bengal resorted to savage means to evict Hindu refugees from an island - known as Marichjhapi in the Sundarbans, situated 75 kilometres east of Kolkata. According to survivors’ estimation, the operation might have led to as many as 10,000 deaths.

The massacre that took place in 1979 is a horrifying instance of human rights violations. Journalist Deep Halder’s book Blood Island: An Oral History of the Marichjhapi Massacre serves as a reminder of the tragedy, which has practically disappeared from public memory.

The victims of the establishment-monitored brutality were refugees from East Pakistan, who had once resettled in Dandakaranya, a place associated with Lord Rama’s days in exile that includes parts of modern-day Telangana, Chhatisgarh, Andhra Pradesh and Odisha. Most of them were Namasudras, who were eager to have a permanent home in West Bengal.

The communists in the opposition in West Bengal continued to voice their support for the refugees until they came to power in 1977. They repeatedly declared that they would help them resettle in the Sundarbans, which was pretty much everything the refugees wanted.

The Jyoti Basu government backtracked on its promises after the Left Front came to power. The entry of refugees into West Bengal was forcibly stopped, although those who managed to reach Marichjhapi toiled hard to turn it into a lively settlement in no time. The island mutated into a place with “rows of huts, a fishing co-operative, a school, salt pans, a health centre, a boat manufacturing unit, a beedi-manufacturing factory and a bakery, with money pooled from their individual savings and some help from writers, activists and public intellectuals sympathetic to their story”. The government, however, held the refugees guilty of unauthorised occupation and also for creating ecological imbalance.

After the government’s efforts to evict the refugees with economic blockade failed – it employed steam launches to ensure that useful supplies couldn’t reach Marichjhapi – it resorted to armed action. Those living in Marichjhapi had experienced loss of lives due to diseases and starvation. Rape of women wasn't unknown to them either. Bullet wounds would lead to many deaths, too. Indescribable brutality was the order of the day as the establishment turned a blind eye to the basic needs of fellow human beings.

The author has a deeply personal association with Marichjhapi. Having barely stepped out of toddlerhood when he had heard of it for the first time from Mana Goldar, a teenager introduced to him as his cousin, had lived with his family for several months. Mana’s father Rangalal Goldar was a leader of the Udbastu Unnayanshil Samiti (Refugee Welfare Committee) that supervised the migration to Marichjhapi from Dandakaranya. Goldar’s activities had forced Mana to live in hiding with the author’s family.

The island in the Sunderbans made frequent returns to Halder’s life since his father helped the refugees, and later, because of a newsroom colleague in Bhopal who had surprised the author with her unexpected Marichjhapi connection. That’s how the idea of writing the book germinated, resulting in revelations that will shock and startle the reader who has probably been in the dark all this while.

Scattered voices speaking in unison - almost invariably - reinforce the poignant reality of the massacre. Part of the substance comes from Halder’s insightful analysis and good research, and the rest from those who know enough about the tragedy that defines the Left Front government’s hour of shame.

Halder has pulled off the improbable by interviewing Kanti Ganguly, the minister of Sunderbans affairs in the Jyoti Basu government. Self-defence and denials are the two key features of Ganguly’s responses. The best he does is acknowledge that “What we (the Left) had promised – that all of them would be rehabilitated in West Bengal – was wrong...And when we were in the opposition we Leftists engaged in some cheap politics and promised them the moon.” Predictably, he doesn’t confess to his guilt.

How the Left Front government approached Marichjhapi and its inhabitants can be summarised in three sentences. They promised. They betrayed. They massacred. Among those Halder met is Manoranjan Byapari, who has lived several lives. Byapari was a Naxal, a rickshaw puller and a cleaner of bhadralok’s toilets, and he is also an author whose books have been appreciated by intellectuals.

Byapari uses no full stops while criticising Basu and his government. He insists that Basu couldn’t ‘tolerate the fact’ that refugees could be self-sufficient without depending on him. “Their (the communists) deal was: “We will give you rice, you vote for us.” Desperate to be acknowledged as champions of the poor, they didn’t want the world to see that “...the poor could very well take care of themselves and ensure their own welfare, if only they weren’t stopped from doing so.” Applauding the virtues of human enterprise would have been the right thing to do. Why it led to the Marichjhapi massacre is a question no Leftist can satisfactorily answer.

Four decades is what it has taken for somebody to write a full-fledged book on a subject that should have been under the magnifying glass of scrutiny long ago. Therein lies the importance of the book, which makes the reader wonder why such a colossal tragedy was discussed in rarely audible whispers for so long.