Movies are a popular vehicle for carrying political messages. And, it is not a new development. Perhaps the present-day makers of biopics or political propaganda movies could take a lesson or two from MGR films to learn how messaging works along with mainstream offerings.

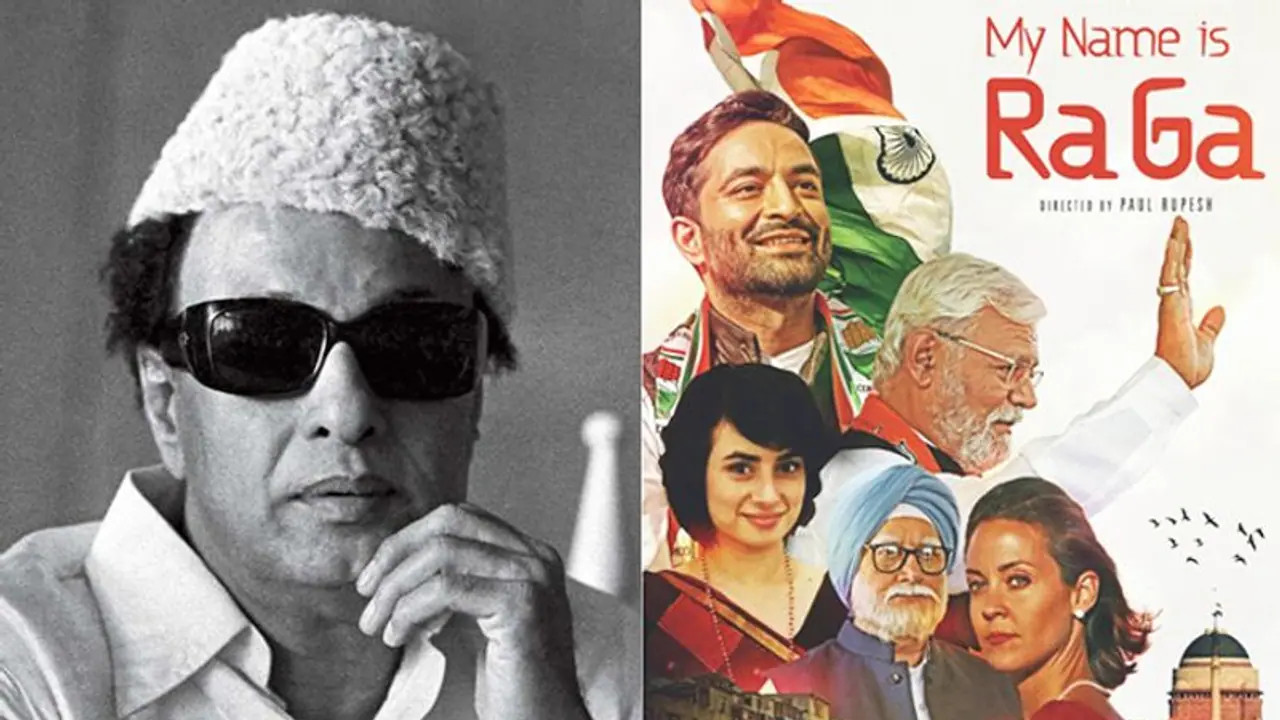

The teaser release of the biopic of Congress leader Rahul Gandhi (My Name is RaGa) a couple of days ago, has once again brought the spotlight on the political propaganda through movies.

It is just not My Name is RaGa. There are a couple of films lined up on Prime Minister Narendra Modi too. One stars Vivek Oberoi, and the other Paresh Rawal.

And The Accidental Prime Minister and Uri, which released a few weeks ago, are also movies that were made with the idea of political messaging.

Down south last week, in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, the film Yathra, featuring Malayalam superstar Mammootty in the lead, hit the screens, and the movie is about the life and times of former Andhra Pradesh chief minister YS Rajasekhara Reddy (YSR).

So, the question that has been doing the rounds is: Are movies the new propaganda tool for politicians?

Films indeed seem to be a popular vehicle for carrying political messages. But, as it happens, it is not a new development.

“Movies with their deep penetration among the masses have always attracted the attention of the politicians, because they are ones, who have to constantly reach out to the public,” said Rajesh Chacko, a Thiruvananthapuram-based professor of history. “Even during the days of the freedom struggle, movies aimed at appealing to the nationalistic sentiments and patriotism of the public were made in many languages. So this is a trend that is almost as old as movies in India,” he added. Kerala and West Bengal have seen many Communist-themed movies.

But post Independence, this fad gradually faded, even though a film like Mother India was produced to counter Katherine Mayo’s unflattering painting of India in the book of the same name.

But in the 1950s, then fledgling Dravidian camp in Tamil Nadu had two young, powerful writers, C N Annadurai and M Karunanidhi, who understood how to combine earthy ideas with lofty bombast and present them in catchy dialogues in workable movie scripts.

Both Annadurai and Karunanidhi had an innate understanding of both movies and messaging, and they infused their films with Dravidian ideology organically without reducing the movies’ sentiment and entertainment quotients in any way.

They questioned the established caste hierarchy and social structures through their movies. The then ruling Congress in the state, with its elitist mindset, looked down upon films and this came in handy for the DMK, which by then had emerged out of its Dravidian progenitor Dravida Kazhagam (DK).

Films like Nallathambi, Velaikari, Or Iravu, and, of course, Parasakthi (which saw Sivaji Ganesan’s debut), with their sharp dialogues (and attractive alliteration) caught the fancy of the public, and movies became one of the main reasons for the DMK to unseat the Congress from power in the state.

And Tamil Nadu has not been the same since then.

Annadurai and Karunanidhi (and to an extent Murasoli Maran) were more focused on ideology, and their work being behind the screens, could not personally project themselves to the public frontally.

But with M G Ramachandran (MGR), who was an on-screen hero, his movies were essentially his platform for political campaigns.

MGR, who was with Annadurai and Karunanidhi before having a fallout with the latter, used his movies to painstakingly create an image of him being a scrupulous leader, a champion of the underprivileged, a fighter for underdogs, a respecter of women, a do-gooder, who never drank or smoked.

All his movie characters had these essential tropes, and his smarts lay in the fact that he could transubstantiate to the masses that his screen persona was also his real-life’s.

“MGR is sui generis for his peerless use of movies to further his off-screen image. The propaganda for himself was never in-your-face. He managed to package it alongside rousing songs and sentiments,” says G Vaidehi, a historian. “No other hero has managed that feat before him or after that. NT Rama Rao’s godly roles in Telugu movies helped him win the approval of the masses in Andhra Pradesh. But his movies were not exactly made with that idea in mind, which was however the case with MGR.”

Perhaps the present-day makers of biopics or political propaganda movies could take a lesson or two from MGR movies to learn how messaging works along with mainstream offerings.

If you had seen Yathra or The Accidental Prime Minister, you will understand artistic subtlety is not their strong suites. By the looks of it, My Name is RaGa, too, is no different.

“Hagiographic presentation, crude caricature of opponents, and crass presentation of politics are what today’s biopics and political movies have become. That is a travesty, especially considering the rich history of the genre in India,” says Vaidehi.