Here are the facts. As per the CBI report published in November 2000, Azhar admitted to match-fixing (for three matches in 1996, which he later publicly denied), and was subsequently banned for life by the BCCI in December 2000. Later, the former captain challenged this ban legally, and in 2012, the Andhra Pradesh High Court declared the life ban illegal

New Delhi: Here’s a simple question. What does the name ‘Mohammad Azharuddin’ mean to you?

For some, he represents the aura of cricket in the late 80s. It was a time most modern-day cricket fans can only imagine, and yet for those who witnessed him in action, Azhar was no less than a magician. Delightful wristwork, superb timing and beautiful footwork – he was ‘God’ on the leg-side.

For others, mostly those who grew up watching cricket in the 90s, he represented the frustration of the 90s. Azhar was captain then, for a long, nearly unending time, and it just seemed that Indian cricket moved listlessly from one bilateral series to another. Perhaps the team was bad, or maybe it was the captain – they only had Sachin Tendulkar and Anil Kumble to rely on.

Also read: Gautam Gambhir blasts BCCI for allowing Azhar to ring bell at Eden

Usually, that is how any – and every – Indian cricketer is defined. When they fade away into the sunset, their legacy – of ability and/or leadership – is most talked about. Azhar, however, is different.

There is no ‘some’ or ‘others’ herein. For every Indian cricket aficionado, Azhar is a source of great pain. He may have been a magical batsman, and a determined captain at times, but both those representations become miniscule in the face of Indian cricket’s greatest tragedy at the turn of this millennium. Yes, one is indeed referring to the match-fixing saga.

Here are the facts. As per the CBI report published in November 2000, Azhar admitted to match-fixing (for three matches in 1996, which he later publicly denied), and was subsequently banned for life by the BCCI in December 2000. Later, the former captain challenged this ban legally, and in 2012, the Andhra Pradesh High Court declared the life ban illegal.

There are some concerns about that particular case – the High Court didn’t consider the CBI report or Hansie Cronje tapes as evidence, and it didn’t really declare Azhar ‘non-guilty’ of any offence. The Court merely upturned the ban, which it deemed against Azhar’s personal interests to pursue a living associated with cricket after a considerable time period.

It is a totally justified action because society doesn’t abide BCCI’s arbitrary rules. We live as per the Indian Constitution and the courts have a responsibility to uphold those laws.

And thus we arrive at this fact – Azhar stayed away from cricket for more than 11 years. It is almost akin to serving nearly 80 per cent of a life-sentence for any heinous crime (which match-fixing was in the eyes of everyone who likes and follows Indian cricket). At most, it can be deemed that Azhar got early parole, if we keep up this likeness to real-life situations.

Here’s the question that has been long coming: was it punishment enough?

The Indian Constitution, and the society as an extension, allows for people who have served their sentence to be rehabilitated. Does it not hold the same for cricket as well? Many other cricketers served shorter bans and have now ventured into cricket coaching or commentating on live television. Is Azhar, having stayed away from the game for more than a decade, not liable to be treated similarly?

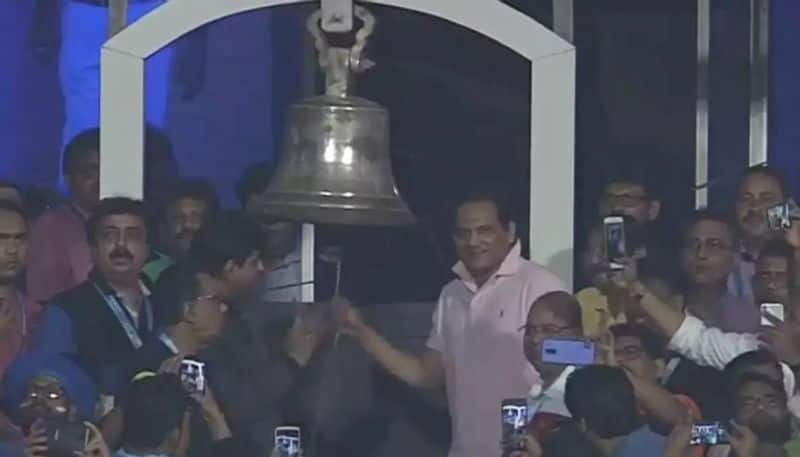

If the answer to these aforementioned questions – in summation to what the High Court ruled in 2012 – is ‘yes’, then Azhar’s return to the cricket fold shouldn’t really be a problem. So, why was there so much brouhaha over ringing the bell at Eden Gardens on Sunday?

Gautam Gambhir’s angry tweet aside, this situation is one of moral ambiguity. On the one hand, Cricket Association of Bengal (CAB) president and former captain Sourav Ganguly wrote to the Supreme Court appointed Committee of Administrators (COA) about how Indian cricket is continuously losing face. He may not have said that directly in his letter, but in attacking the COA’s policies and indecision over many administrative issues about both international and domestic cricket, that is clearly the implication here.

India may have won today at Eden but I am sorry @bcci, CoA &CAB lost. Looks like the No Tolerance Policy against Corrupt takes a leave on Sundays! I know he was allowed to contest HCA polls but then this is shocking....The bell is ringing, hope the powers that be are listening. pic.twitter.com/0HKbp2Bs9r

— Gautam Gambhir (@GautamGambhir) November 4, 2018

As such, how can the CAB – when taking a moral high ground against the COA through its leader – invite someone with a tarnished image to do the honours at an international game staged at the Eden Gardens, the spiritual home of Indian cricket? Again, this isn’t about Azhar. The court has reinstated his rights, but surely there is no compulsion on any cricket body to endorse the same, especially when in the eye of a reformation storm.

This issue is representative of the heady times BCCI – and Indian cricket as a whole – is going through. There is no right answer here, just there needs to be a propensity to stay on the right side of things. For, this whole process undertaken directly in the Supreme Court’s purview and under COA’s authority is about mopping up any muck that has been sticking to the game in this country. At this point in time, surely it makes sense to wait a while before re-uniting with those who have hurt cricket in India.

Rehabilitation and re-inclusion – be it of tainted cricketers like Azhar or even former administrators, never mind their rich contributions – can be postponed until such a time as to when this process is complete and the BCCI comes out pristine from this judicial review.

Or, is that too much to ask?

Last Updated Nov 6, 2018, 3:07 PM IST

![Salman Khan sets stage on fire for Anant Ambani, Radhika Merchant pre-wedding festivities [WATCH] ATG](https://static-ai.asianetnews.com/images/01hr1hh8y86gvb4kbqgnyhc0w0/whatsapp-image-2024-03-03-at-12-24-37-pm_100x60xt.jpg)

![Pregnant Deepika Padukone dances with Ranveer Singh at Anant Ambani, Radhika Merchant pre-wedding bash [WATCH] ATG](https://static-ai.asianetnews.com/images/01hr1ffyd3nzqzgm6ba0k87vr8/whatsapp-image-2024-03-03-at-11-45-35-am_100x60xt.jpg)