An Asian Games medallist selling tea and driving an auto-rickshaw to make ends meet is enough to shock the nation, which thus far could hardly care less about the game called sepak takraw and its practitioners

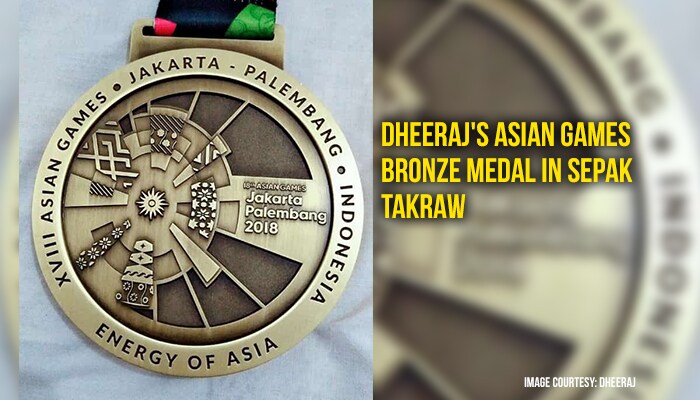

"Yeh medal mera career ka sabse heavy medal hai (this medal is the heaviest of my career)," says Harish Kumar, taking his prized possession out from his almirah. "Can I touch it?" I ask, tempted by that once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. After all, it was a piece of metal that fires the best of athletes to outdo themselves and is a culmination of their years of hardship and sacrifice. It was an Asian Games bronze medal, no less.

"

"Sure, here you go," says Harish, passing the medal on to me. The medal is h-e-a-v-y. I don't know whether he meant it or not, but the heaviness of the medal is true metaphorically as well. It not only brought into the limelight a game called sepak takraw that nobody in India would have known, the medal has changed lives. Had it not been for the medal, the nation's media that still doesn't deem it necessary to look beyond cricket and a few other sports, would never have thronged to these squalid neighbourhoods, never have come to know of the heroes that reside here.

We are at Delhi's Majnu Ka Tilla — known as a colony of Tibetan refugees and some of the most downtrodden sections of the local population. It is an area pockmarked by dusty, narrow lanes and bylanes; small, dingy rooms housing many more than their carrying capacity. Some of the lanes are so narrow that the only way you can move through them is by walking sideways. Garbage is strewn all around and you would have to hop over cow dung. You would hardly get mobile network inside those serpentine lanes, and internet is still an alien word for most of the residents. And with nightfall, the place is known to become a haven for drunkards and drug addicts. It is a gloomy, gloomy atmosphere. The rusty and dilapidated shed at the bus stand is symbolic of the state the place is in and adds to the melancholy. It is an area almost hid from the world, an area that doesn't figure in the consciousness of the nation's English-educated elite.

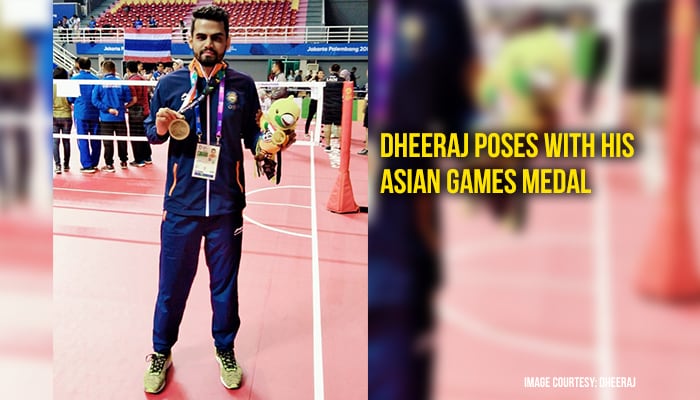

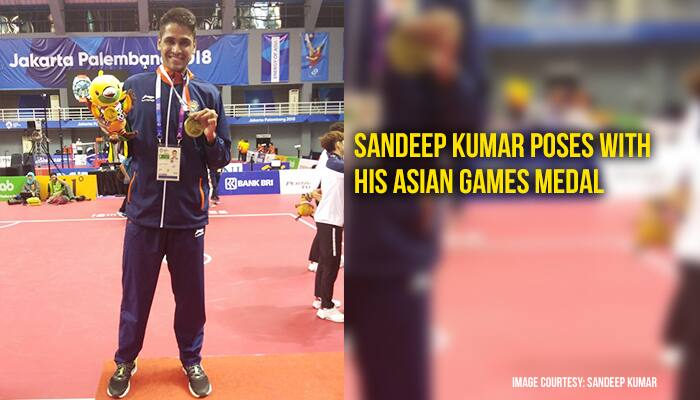

Yet, this locality today is the talk of the town. For it houses four such gems, the brightness of whose lustre has travelled far and wide. MyNation tracked down the four heroes of the nation — Harish Kumar, Dheeraj, Sandeep Kumar and Lalit Kumar — who won bronze as part of India's sepak takraw team in the recently-concluded Asian Games in Indonesia and interacted with them and their families. And what we learnt is sure to bring a tear to the eye.

"Main bahut gareeb family se belong karta hoon (I belong to a very poor family)," says Harish. "My father is an auto-rickshaw driver. He drives an auto-rickshaw on rent. Some days he gets to drive, some days he doesn't. My mother works as a domestic help. My father owns a small tea stall. On days when he doesn't get an auto, he works at the tea stall. Sometimes I work at the tea stall too, sometimes my elder brother Naveen runs it."

An Asian Games medallist selling tea and driving an auto-rickshaw to make ends meet is enough to shock the nation, which thus far could hardly care less about the game called sepak takraw and its practitioners. This strange-looking game was considered no more than a leisurely activity. To pursue a career in it was seen as a terrible waste of time. And indeed that is what the neighbours of Harish and Co used to say.

"Aas pados ke log bolte the is game mein kuch nahi hai, kya karoge? Saradin aise hi khelte rehte ho, kuch kaam dhanda karo (the neighbours used to tell me there is nothing to be achieved by playing this game and that I should not waste my time playing around all day, but focus on getting a job," Harish says. "They also used to say that our coach was looting our money," he adds.

Dheeraj, Sandeep and Lalit shared this experience. All of them have seen tremendous hardships to reach the level that they have.

"The neighbours used to taunt us and say that we used to move around like vagabonds. I ignored those comments. I believed in paying back with my work. I knew one day I will make my country proud," says Sandeep. "There was no dearth of people who would discourage us," adds Dheeraj.

However, the Asian Games triumph has led to a sea change. "Aaj jo log taana dete the, wahi log humein salam karte hain, aur phoolon ke mala se swagat karte hai (the same people who used to taunt us, salute us and welcome us with garlands now)," says Harish.

"I am recognised wherever I go. Those people who used to taunt us are happy for us now. I belong to a very backward community. People, who used to mock me, tell me now that I have made our community proud," adds Lalit.

The amount of trouble the four Asian Games medallists had to go through is difficult to even imagine. None of them had it easy to convince their poverty-stricken families that there was merit in not only taking up such a nondescript sport like sepak takraw but taking it up as a career. There was no surety that the game would help in earning a steady income, and for families that didn't know from where the next meal would come from, sacrificing one able-bodied member to sepak takraw was a luxury they could have ill-afforded.

For Harish, the situation was particularly bad. His sister and one of his brothers are blind. Two of his elder brothers had been sportsmen but suffered injuries that ended their careers. One of them, Naveen, had played sepak takraw at the international level too. This makes Harish's contribution to the family's income absolutely necessary. Thankfully for the Asian Games achievement, he would now be able to take some worthwhile part in running the family, but his biggest handicap is that he still doesn't have a regular job. That is where he lags behind his India teammates, Sandeep, Lalit and Dheeraj, all three of whom are employed with the Sashatra Seema Bal.

There were times when the poverty had become so unbearable and the lack of recognition for a player of sepak takraw so galling that he had wanted to quit.

"Monetary issues started to crop up. Bahar jaane ke liye toh thoda bahut apne jeb me bhi paisa hona chahiye (you need at least some money in your pocket to go outside). My mother had once borrowed Rs 150-200 and gave it to me. It hurt me that my mother had to borrow money for me. We didn't have money. My father used to say, 'Leave this game, you will achieve nothing by playing this'. I felt like quitting the game," Harish confesses.

"I used to tell him that there is nothing to be gained from playing this sport and that he should concentrate on his studies and look for a job, otherwise how will we be able to sustain ourselves?" Harish's father Mohanlal says.

Harish's mother reveals that she would make chutney with chilli and garlic and that was all that Harish could carry with him as food when he went away for matches. "At times I wouldn't have money for his medicine. At times he would not have shoes of his own. He would wear the neighbours' shoes or move around barefoot. I used to give him whatever money I could, whether it's Rs 2 or Rs 10. He used to save from that and give me back. I used to borrow money to give to my children. My kids used to feel sad seeing their mother borrowing from people. Harish never went in the wrong track, for which I am extremely proud. He has made the society proud," Harish's mother says, her voice choking with emotion.

Lalit too has a sad tale to tell. "I didn't have money to go for practice. I used to get a daily allowance of Rs 10. However, I was always determined to go to the stadium for practice. If I spent those Rs 10 while going to the stadium, what would I eat in the evening? That was a constant worry. My father used to say that I had not studied well and I should look for a job to support the family, as his health was worsening. At times I used to go for practice without food. I used to walk on foot to save money, and ask motorcyclists for 'lift'. When the motorcyclists didn't help us, I used to hitchhike on trucks. Then I used to walk from where they would drop me. I used to go through a whole lot of difficulties but somehow had to reach the stadium for practice.

Sandeep has a similar story. "At times I didn't have money to go for practice. There were compulsions, which I shared with my coach, Hemraj sir. He told me to go to his house and take Rs 20 from his wife. I felt embarrassed. I told him that I couldn't ask for money. But sir told me, 'Don't skip practice. Skip meals if you have to, but not practice'. There were times when I would hide from the conductor in a bus because I didn't have the fare with me. But I somehow wanted to reach the stadium so that I can practise.

Like Harish, the thought of quitting crossed the minds of Lalit and Dheeraj as well at one time or the other.

"In 2009, I became quite demoralised. I had been playing the sport for some time but was yet to achieve anything really worthwhile. Hemraj sir counselled me against quitting. He said, 'Don't lose heart, you will get your chance someday or the other'," says Lalit.

"There have been a number of times that I had wanted to give up. I had played in the 2014 Asian Games in Incheon too, but unfortunately, we could not win a medal there. The times after that was really difficult. There was no job, no recognition. I used to feel despondent. I was getting older and was not getting much support. We did not have money to even arrange for food. Father was getting older too. I used to be extremely anxious," says Dheeraj.

The Delhi government, a few days back, raised the reward amount for the Asian Games achievers to Rs 1 crore (from Rs 20 lakh) for gold medallists, to Rs 75 lakh (from Rs 14 lakh) for silver medallists and to Rs 50 lakh (from Rs 10 lakh) for bronze medallists. Chief minister Arvind Kejriwal also assured jobs for all the Asian Games winners.

A job in Delhi is indeed what Harish and family desperately want. "My appeal to the government is that I get a job so that I can support my family and bring medals for the nation as well," Harish says.

"If my younger brother Harish gets a job, or some financial help from the government, our father won't have to work at a tea stall. Nobody wants to live in poverty. We hope Harish gets a government job in Delhi. No international player would want to work at a tea stall. If he is freed from such burdens, he can practise for eight hours instead of the four hours he is doing now. If he is able to practise more, he would be able to win gold in the next Asian Games. But whatever happens, he will continue to bring medals for the nation," Naveen says.

Lalit and Sandeep want sepak takraw players to be eligible for employment in government agencies apart from SSB too. That is necessary for the game to develop in India, they say.

Dheeraj revealed that the Union government had rewarded the nation's sepak takraw team for bringing home a medal that no one expected.

"We had visited the prime minister's residence too. There was a programme organised at the Ashoka hotel by the sports ministry. Home minister Rajnath Singh and sports minister Rajyavardhan Singh Rathore and a number of other ministers were there. All of them praised us a lot. It was a moment of great pride for us. The bronze-medal-winning Indian team was awarded Rs 60 lakh by the sports ministry. We met Modi sir too," he says.

"The government has supported us a lot," Harish says. "Our coaches and the secretary-general of our federation Yogender Singh Dahiya have helped us a great deal too. He used to provide us with facilities. When we didn't have money to go to the nationals, he used to provide that too."

However, given that most of the support is being provided to Harish and Co after the Asian Games fame, one wonders what support they had had when they were getting ready for the Games.

"At that time, we had the support of our coaches, and the secretary-general of the federation helped us a lot. Our diet at the Indian camp was quite good. We had a two-month-long camp in Thailand too. There we had a foreign coach, and learnt new techniques that were not in use in India," Harish says.

All four players made a mention of the help from the Sports Authority of India (SAI) in the form of money, kits and good practice. They are also beholden to Hemraj for bringing them into this sport, supporting them with funds and proper facilities and motivating them whenever needed.

From practising on barren, gravelly fields dotted with cow dung, with a ball made out of rubber tubes, and without nets or proper shoes, to setting the courts on fire in Indonesia, Harish, Sandeep, Lalit and Dheeraj have come a long way. But have their lives become any better? Yes, they have become famous after the Asian Games, but one can't sustain on fame alone.

"I have never craved for fame. I was just engrossed in my game. I just utilised whatever opportunities I got. Wherever Hemraj sir used to ask us to go, we went and brought home medals too. After that, we had to fill up forms for scholarships. We were happy with all these," Harish says. But the nation can't let its sports heroes rot in penury.

The nation needs to feel ashamed at the apathy it has had towards sports that are not too well-known, as much as it needs to feel proud of the champions of those obscure disciplines.

Last Updated Dec 10, 2018, 11:59 AM IST

![Salman Khan sets stage on fire for Anant Ambani, Radhika Merchant pre-wedding festivities [WATCH] ATG](https://static-ai.asianetnews.com/images/01hr1hh8y86gvb4kbqgnyhc0w0/whatsapp-image-2024-03-03-at-12-24-37-pm_100x60xt.jpg)

![Pregnant Deepika Padukone dances with Ranveer Singh at Anant Ambani, Radhika Merchant pre-wedding bash [WATCH] ATG](https://static-ai.asianetnews.com/images/01hr1ffyd3nzqzgm6ba0k87vr8/whatsapp-image-2024-03-03-at-11-45-35-am_100x60xt.jpg)