To these worthies, CBI's ex-director Alok Verma and ex-special director Rakesh Asthana have been bad and good at different points of time, determined by political exigencies

It’s a season of flipflops. As ‘CBI vs CBI’ has turned a popular discourse of the nation, MyNation reported how the Congress’s Mallikarjun Kharge, who has shot off a four-page letter to Prime Minister Narendra Modi, objecting to CBI’s ex-director Alok Verma’s forced leave, had in January 2017 objected to his appointment. But Kharge is not alone in this show of duplicity.

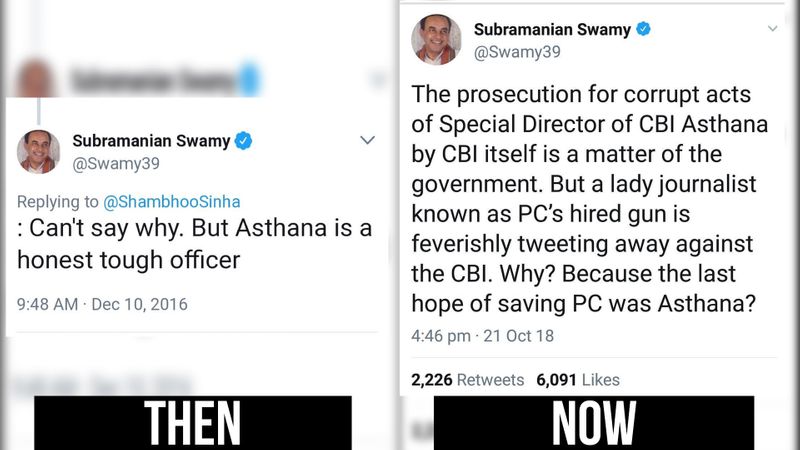

Subramanian Swamy

The BJP Rajya Sabha MP is known to voice his views regardless of the party’s stand on different issues. But this time, he has gone a step further and done a volte face. Swamy had, in a tweet posted on December 10, 2016, backed Rakesh Asthana, the ex-special director of CBI who has been sent on a forced leave along with Alok Verma. Swamy endorsed him, calling the senior cop an “honest” officer. But now, after the controversy broke out, Swamy is seen accusing Asthana of shielding former finance Minister P Chidambaram (who is referred to as PC by many). Chidambaram is an accused in the case of Aircel-Maxis scam.

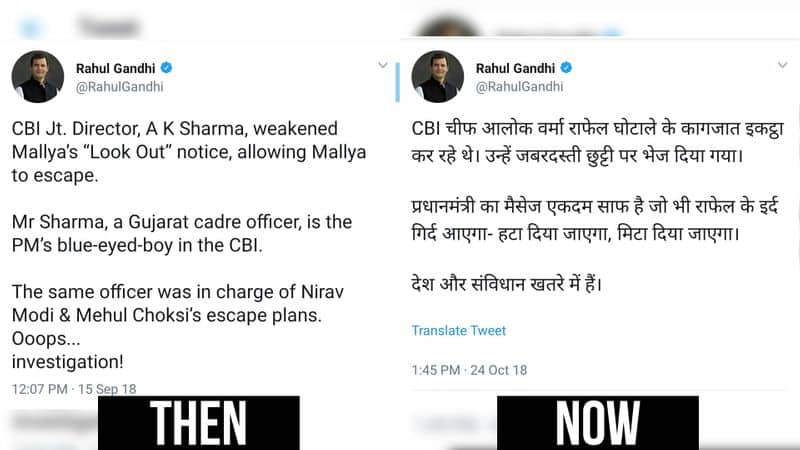

Rahul Gandhi

Though not as blatantly as his leader of the House in Rajya Sabha Kharge, Congress president Rahul Gandhi has softened his stance, too. This September, Gandhi had posted a tweet accusing CBI joint director AK Sharma of “weakening Mallya’s lookout notice”. He had alleged that Sharma, who is a Gujarat cadre officer, was Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s “blue-eyed boy in the CBI”.

Gandhi made a strong allegation that Asthana “allowed (Vijay) Mallya to escape”, adding that he facilitated scam accused Nirav Modi and Mehul Choksi to flee the country. Today as he is defending Alok Verma’s transfer, he is also protesting the transfer of 13 key officers, one of whom is the same Sharma that Rahul Gandhi called PM’s “blue-eyed boy”.

That is not all. Gandhi has done a volte-face on Verma as well. When Kharge wrote to the Prime Minister, objecting to Alok Verma’s appointment as CBI director, he did so on behalf of the Congress. That letter, therefore, demonstrates Gandhi’s somersault as much.

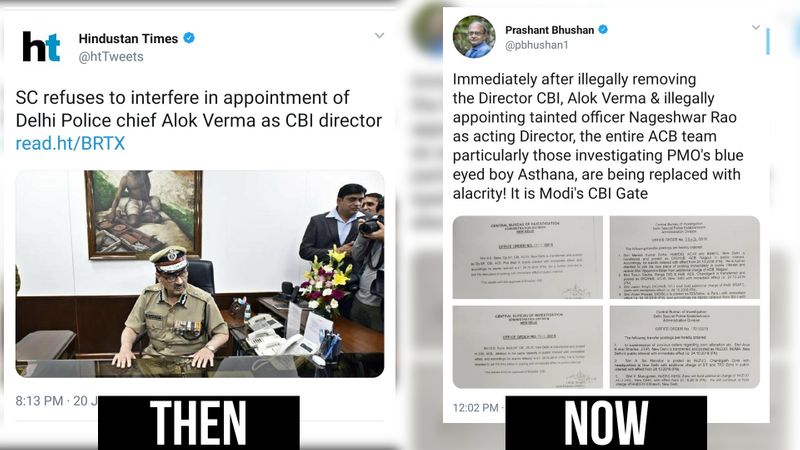

Prashant Bhushan

His is one voice that is more often than not found in the courtrooms challenging government decisions. Back in January 2017, almost at the same time when Mallikarjun Kharge wrote a three-page dissent note against Verma’s appointment as the CBI director, Bhushan moved the apex court, asking for the minutes of the meeting between the Prime Minister, then Chief Justice Dipak Misra and leader of the largest opposition party (the Congress) that chose Verma as the next head of India’s premier investigative agency.

Though Bhushan did not oppose Verma’s appointment in as clear terms, he insinuated enough. In his petition, the activist-lawyer argued that the Union government had taken a series of “mala fide” steps to curtail the scope of another contender RK Dutta.

It’s another story altogether that not only Mukul Rohatgi, the then attorney general, rubbished the allegations but the Supreme Court bench of Justices Kurien Joseph and AM Khanwilker junked the petition, too.

Whether the Centre should have launched a midnight coup at the CBI, whether Verma and Asthana should have been unceremoniously sent packing or whether the CBI feud should have been allowed to reach such a stage where the country’s premium investigative agency had to raid its own office can be debated. What’s undebatable is that volte face is a part of our politicians’ character cutting across party lines.

Last Updated Oct 25, 2018, 9:20 PM IST

![Salman Khan sets stage on fire for Anant Ambani, Radhika Merchant pre-wedding festivities [WATCH] ATG](https://static-ai.asianetnews.com/images/01hr1hh8y86gvb4kbqgnyhc0w0/whatsapp-image-2024-03-03-at-12-24-37-pm_100x60xt.jpg)

![Pregnant Deepika Padukone dances with Ranveer Singh at Anant Ambani, Radhika Merchant pre-wedding bash [WATCH] ATG](https://static-ai.asianetnews.com/images/01hr1ffyd3nzqzgm6ba0k87vr8/whatsapp-image-2024-03-03-at-11-45-35-am_100x60xt.jpg)